We often hear that the first casualty of war is the truth. Yet the truth cannot be killed. What can be killed is our capacity for critical thinking. The public discourse about the Ukraine war has made this abundantly clear.

Over the past year, self-described progressives have rushed to embrace allegations that Russian forces have committed atrocities in Ukraine, yet many of these allegations have been based on ambiguous evidence, or no evidence at all.

A lawyer’s approach to allegations of criminality

I have practised law for three decades. For most of that time, I have been a litigator. Overwhelmingly, my clients have been ordinary citizens who claimed to be the victims of corporate misconduct. To represent my clients successfully, I have had to persuade neutral arbiters that, based on the admissible evidence, my clients’ allegations of wrongdoing were likely to be true.

To that end, and on countless occasions, I have tested and evaluated the credibility of witnesses, identified contradictions and gaps in the available evidence, and weighed alternative hypotheses when the evidence supported, as it often does, more than one hypothesis. In short, my duties as legal counsel obliged me to engage in critical thinking.

Of course, a lawyer’s training does not make lawyers infallible. Lawyerly assessments of evidence do not guarantee the discovery of the truth, but they do lead to the truth far more often than superficial assessments of the evidence, or blind faith in the veracity of the accusers.

I approach allegations of atrocities against Russia’s military forces just as I approach all allegations of wrongdoing – with a critical lens. So should we all.

A case study in critical thinking about the Ukraine war

In October of last year, I received a text message from a long-time friend of mine. She is a devoted leftist and a passionate anti-imperialist. For many years, she has had a strongly negative perspective toward the Russian government.

Her text was brief. It consisted of a link to a newly published report in the Guardian, along with one word: “terrible”. Her terse message suggested to me that she believed the allegations published by the Guardian to be true.

I clicked on the link and up popped an article titled “Russian troops kill Ukrainian musician for refusing role in Kherson concert.”

The article’s title was framed definitively, as if the murder had been proven. So too was the subheading, which read “International condemnation swift after conductor Yuriy Kerpatenko shot dead in his home.” Neither the title nor the subheading used the word ‘alleged’ or described the article’s central thrust as a ‘claim’ or an ‘accusation’.

In the article’s first paragraph, however, the Guardian’s Kyiv-based reporters, Charlotte Higgins and Artem Mazhulin, revealed that the source for their report was the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture, which had just published the accusation on its Facebook page.

Is Zelensky’s government a credible source of information about the Ukraine war?

Because the Guardian‘s article was based on the Culture Ministry’s Facebook page, I considered myself duty-bound to consider the credibility of Ukraine’s government.

Ukraine’s government is profoundly dependent on the support of Western states. Earlier this month, the European Union’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, stated publicly that Ukraine would fall “in a matter of days” if the West stopped supporting Ukraine. Days later, Germany’s Minister of Defense Boris Pistorius expressed a similar view, stating “If we stopped deliveries of weapons to Ukraine today, the end of Ukraine would come tomorrow.”

Thus, for Ukraine’s government, the continuation of Western support is of existential importance.

The Zelensky government undoubtedly understands that, in the West, widespread public opposition to arming Ukraine would make it far more difficult, if not politically impossible, for Western governments to continue the flow of weapons to Ukraine. Indeed, by June of last year – a mere four months into Russia’s invasion – Zelensky’s government was already worried that “war fatigue” might erode the West’s resolve to sustain the transfer of weapons.

How does a government that depends for its very existence on Western aid ensure robust levels of public support for sending more weaponry? The answer should be obvious to any rational and objective observer: by inflaming Western public opinion against Russia.

Ukraine’s government has a profound interest in convincing Western voters that Vladimir Putin is the new Hitler, that innocent Ukrainians are being subjected to monstrous crimes, and that, if Ukraine falls, NATO countries will soon face a ferocious assault from the Russian horde.

These considerations do not mean that every allegation levelled against Russia by Ukraine’s government is false. On the contrary, in any given case, and absent evidence to the contrary, it is at least possible that Ukraine’s government is telling the truth. The point here is simply that Ukraine’s government has a powerful motive to lie, to exaggerate, to present hypotheses as proven facts, and to misrepresent or conceal relevant evidence. Any government that is dependent for its very existence on massive external support would have precisely the same motive.

Ultimately, Ukrainian government allegations against Russia, standing alone, possess little to no evidentiary value. Unless Ukrainian government allegations are corroborated by independent, objective and credible evidence, a critical and fair-minded observer would view those allegations merely as unproven assertions of criminality, and nothing more.

Did the Guardian provide independent, objective and credible evidence to support the Culture Ministry’s accusation?

According to the Culture Ministry’s Facebook post (a link to which was included in the Guardian’s article), its accusation that Russian soldiers murdered Kerpatenko was based on a report by a journalist named Olena Vanina. The Guardian‘s article makes no mention, however, that Vanina was the source for the Culture Ministry’s accusation. Moreover, the Culture Ministry’s Facebook post did not include a link to or copy of Vanina’s report.

Furthermore, the Guardian’s reporters cited no evidence to support the accusation that Russian soldiers murdered Kerpatenko. The closest they came to doing so was a statement in their article that unidentified “family members” of Kerpatenko claimed to have lost contact with Kerpatenko in September (the month prior to Vanina’s report of the alleged murder). According to the Guardian, the information that family members had lost contact with Kerpatenko in September came from the Kherson regional prosecutor’s office. In other words, it appears that the Guardian reporters themselves did not speak to Kerpatenko’s family members.

Standing alone, Kerpatenko’s disappearance does not prove that he was murdered in cold blood by Russian soldiers. He might have been imprisoned. He might have gone into hiding, either out of fear of Russia’s military or for reasons that were unrelated to Russia’s military. He might have been killed in self-defence by Russian soldiers. Kerpatenko’s disappearance in September is consistent with these and other alternative hypotheses.

There is, moreover, no discussion in the Guardian’s article of the response of Russia’s government to Vanina’s grave allegation. The Guardian reporters never tell us whether Russia denied the allegation or was even afforded an opportunity by the Guardian‘s reporters to respond to the allegation. Assuming that the Guardian’s reporters gave no such opportunity to Russia’s government, they offer no explanation as to why they did not seek a response from Russia’s government.

If all these factors do not suggest journalistic bias to you, then consider this: the Guardian’s article consists of twenty-one paragraphs, and sixteen of them consist of condemnations of the alleged crime from Ukrainian or Western figures from the artistic community. Their commentary is rife with highly inflammatory language, including “pure genocide”, “brutal murders”, “sickening”, “hunting activists”, “enslaved countries” and “destroying culture”. Every single condemnation repeated by the Guardian presupposed Russian guilt, when in fact the Guardian‘s article presented no credible evidence to establish Russia’s guilt.

What about Olena Vanina?

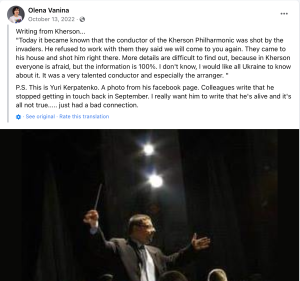

Google searches of the name Olena Vanina lead to a report in Ukrainska Pravda which discusses Vanina’s claim that Russian soldiers murdered Kerpatenko. That report provides a link to the Facebook post in which Vanina first reported the alleged murder of Kerpatenko:

As can be seen from her post, Vanina asserts that the “invaders” came to Kerpatanko’s house and “shot him right there”. She states that the information is “100%”, while at the same time admitting that “more details are difficult to find out, because in Kherson everyone is afraid”.

Based on Vanina’s post, it seems clear that she did not witness the alleged murder, nor does her post state that she communicated with one or more eyewitnesses to the alleged murder. We simply have no idea who Vanina’s sources are. In effect, Vanina asked her readers simply to trust that her accusation is “100%”.

An entry relating to Kerpatenko and his alleged murder has been created on Wikipedia. That Wikipedia entry refers to numerous English-language articles published by mainstream media organizations other than The Guardian, but only one of them (a Times article discussed below) adds to the body of evidence underlying the allegation that Russian soldiers murdered Kerpatenko.

One of the articles referenced by Wikipedia raises additional questions. That article was published in the Ukrainian language by the Ukrainian news website, Obozrevatel. Obozrevatel is owned by Ukrainian businessman Mykhailo Brodskyy, a Ukrainian politician who was jailed on corruption charges in the 1990s. According to the Deepl translation of the Obozrevatel article:

Friends still do not know when the murder took place. Perhaps back in September, because on his birthday, September 9, he did not respond to his friends’ Facebook greetings.

Many thought that there was simply no internet in Kherson. The news of the musician’s death was first reported on October 12 [Vanina’s Facebook post is dated October 13]. Yuriy Kerpatenko was shot dead with a burst of gunfire through the door of his apartment.

According to his friends, Yuriy lived with a woman, and her daughter was also in the apartment. She suffered a severe wound to the face. The woman herself says she doesn’t remember anything.

Thus, the one person who appears to be an eyewitness to the alleged murder “doesn’t remember anything”. Also, the Obozrevatel article implies that the daughter of Kerpatenko’s partner survived the attack, yet it discloses no further information about the daughter’s whereabouts, nor does it disclose whether Obozrevatel made any attempt to speak directly with the daughter. All the information relating to Kerpatenko’s partner and her daughter appears to have been provided to Obozrevatel by unnamed friends of Kerpatenko. The Obozrevatel article does not explain how Kerpatenko’s unnamed friends acquired that information.

Notably, the Obozrevatel article was published on October 14, 2022. For unknown reasons, the Guardian‘s article, which was published on October 16, 2022 (two days later), makes no reference to the alleged wounding of the daughter of Kerpatenko’s partner, or to the report that the daughter remembers nothing about the alleged attack.

The Times tells the “true story” of Kerpatenko’s death

On November 19, 2022, the U.K.’s Times published an article in which it purported to tell the “true story” of Kerpatenko’s death. Titled “Martyred for his music? The outspoken Ukrainian conductor shot dead by the Russians“, the article reported that the circumstances of the conductor’s death are “murkier, more complicated and tragic than had at first been understood.”

The Times article was based on interviews in Kherson of half a dozen of Kerpatenko’s former colleagues, as well as police, prosecutors and neighbours. The interviews were conducted in mid-November, approximately one month after the initial reports of Kerpatenko’s alleged murder were published by Ukraine’s Culture Ministry and Western media. None of the persons interviewed by the Times purported to have witnessed the killing.

According to the Times:

[Kerpatenko] was not a fervent Ukrainian patriot. Rather, his colleagues said, his political views tended towards nostalgia for a lost imperial Russian past, a time of great poetry, literature and towering composers like Pyotr Tchaikovsky whom he admired so much. He despised modern Russia, which he saw as the offspring of the repressive USSR, and believed that Ukraine was the best option available.

Apparently, Kerpatenko had a fondness for tsarist Russia.

The Times continues:

In 2011 [Kerpatenko’s] dreams were shattered when his wife, Lena Moseychuk, a violinist from Kherson, died of cancer. Kerpatenko was devastated. After that, colleagues said, he began to drink heavily, and became more belligerent and demanding.

Yet, for all his faults, they remember his genius. “He was so talented,” said Uvarova. “He really was.”

After his death, tributes came from across the Ukrainian arts world, where his work was widely respected.

Yet for the last months of his life, Kerpatenko — isolated and furious — sank into a poisonous spiral. The strain of the occupation, and of not being able to create, hung heavy on him, driving him to ever more destructive behaviour.

By September, Kerpatenko “was in a bad way”. He and his partner “were both drinking heavily and becoming progressively more reckless in showing their hatred of the occupiers. ‘From his birthday onwards they went on a binge,’ said one of his upstairs neighbours.”

On September 27, the final day of a referendum in Kherson on whether the region should become part of Russia, Kerpatenko and his partner went out drunk and were seen “hitting the ballot boxes”, said one of their neighbours.

According to the persons interviewed by the Times, six Russian men in uniform came to Kerpatenko’s flat the next morning:

They banged on the grey metal door, shouting for him to open up.

Across the hallway his neighbour Raia, 75, heard a loud noise. She opened the door and saw the men in uniform. “They told me to get back in the house and they wouldn’t touch me,” she said.

Raia shut the door. Then she heard two shots, followed by a burst of automatic gunfire. When she came back into the corridor, she saw Kerpatenko lying crumpled on the cold concrete floor outside his flat. There was “something in his hand”, she said. “And a man looked out of the room, I don’t know who he was . . . and he said ‘Grandma, get back to your apartment’. I asked, ‘What is that in his hand, a gun?’ He said, ‘Yes, a machinegun’.”

[…]One neighbour said that when she saw Kerpatenko’s body that morning, he was cradling a Kalashnikov in one hand.

None of the people we interviewed believed that Kerpatenko owned an assault rifle. Several of his neighbours and former colleagues said that they thought it was more likely that the Russians had planted the gun on him after killing him.

The conductor’s former colleagues and neighbours do not think that he was killed directly because he told the Russian occupiers that he would not perform with the orchestra. Nobody else we spoke to who made the same decision had even been threatened.

Rather, they believe that Kerpatenko’s public pro-Ukrainian position, his anger at the occupiers and his belligerence, along with his refusal to perform, led to the raid on his house and to his death.

Just like the Guardian, the Times appears to have made no effort to obtain a response from the Russian government to the allegation that Russian soldiers murdered Kerpatenko. The Times offers no explanation for its apparent decision not to seek such a response.

What happened to Yuriy Kerpatenko?

To date, human rights organizations have accumulated persuasive evidence that both Russian and Ukrainian forces have committed war crimes. This should surprise no one, because war makes monsters out of men. Atrocities are an inevitable feature of war. That is why we should do everything in our power to prevent war, and everything within our power to end it by peaceful means when we fail to prevent it. That is also why we should hold all war criminals accountable when the evidence establishes their guilt.

As regards Yuriy Kerpatenko, however, the publicly available information leaves key questions unanswered.

For example, none of the persons interviewed by the Times believed that Kerpatenko owned an assault rifle. They report, however, that, in the months leading up to his death, Kerpatenko was “isolated and furious” and “sank into a poisonous spiral”, “driving him to ever more destructive behaviour.”

In such circumstances, it is at least plausible that Kerpatenko engaged in threatening and potentially lethal behaviour when Russian soldiers appeared at his door.

At the end of the day, it remains far from clear what happened to Kerpatenko.

The tragic case of Yuriy Kerpatenko highlights the necessity of withholding judgment on allegations of criminality until a full, impartial and professional investigation has been conducted. In the fog of war, our overwhelming tendency is to render snap judgments that conform to our own biases and preconceived notions of ‘the enemy’. This tendency makes dialogue with ‘the enemy’ extremely difficult.

If a full and impartial investigation supports the allegations that Russian soldiers killed Kerpatenko in cold blood, then they should be prosecuted in accordance with due process of law.

In the interim, the cause of peace and justice will not be served by a stampede to judgment. Each and every allegation of criminality should be assessed on its own merits. No one’s guilt should be assumed.

The war in Ukraine might well degenerate into a nuclear exchange. As such, this war constitutes an existential threat to humanity. Our ability to think critically and objectively, and to withhold our judgment until all the facts are known, is our best protection against mutual annihilation.

[A slightly modified version of this article was originally published by Canadian Dimension on May 30, 2023.]

great arrticle Dimitri and superb media criticisms right now. with this war one of the most difficult elements when engaging with people and pushing back against junk journalism and what not, is the west’s use of half truths which are the most difficult to debunk because there is SOME TRUTH that Russia is or has engaged in human rights abuses, that there are legitimate grievances Ukraine and the region of Eastern Europe and asia has against Russia, and the state of Putin isn’t the most democratic certainly not be Western liberal standards. But that said the same is also true of the other side and what’s left out entirely and this is due to the NGOs and practices like this, is Western imperialism and decades of that used in Ukraine and the region of Eastern europe and even Russia and all these semi-NGOS where when you trace the source its all junk coming from professional liars and state terrorists known as Western imperial governments. anywho great post, sad story about this man, may his killers be brought to justice, and i’ll just say although I understand russia’s actions completely, Russia out of Ukraine but NATO out of existence.