In 2014, the Canadian polling firm EKOS asked respondents whether they agreed with the following proposition:

If the current patterns of stagnation among all except those at the very top continue, I would not be surprised to see the emergence of violent class conflicts.

EKOS found that 57% of Canadians endorsed that view.

And why shouldn’t Canadians endorse that view?

As Martin Lukacs recently observed, between 1980 and 2015, the real income of the richest 1% of Canadians more than doubled, and that of the richest 0.1% almost quadrupled. Meanwhile the real income of Canadians in the bottom 90% flatlined during that period.

Moreover, since Justin Trudeau assumed office in 2015, the amount of money the richest Canadians horde in offshore tax havens nearly doubled to $353 billion.

Lukacs explains:

Just months before becoming prime minister, Trudeau offered a warning at the Canadian Club of Toronto, the ritziest lecture series on Bay Street: a backlash against the elites was looming, if confidence in the economic system could not be rebuilt. The country needed a plan “aimed squarely at restoring that sense of fairness,” he told the assembly of financial elite, otherwise “Canadians will eventually entertain more radical options.” A hush fell over the room. Trudeau asked for their support for a modest “tax hike on the one percent,” allowing him to channel the rhetoric of the Occupy movement.

This was the maneuver the Liberal Party succeeded in pulling off in that year’s election: building buzz about how a Trudeau victory would be an anti-establishment breakthrough, while signaling to the business elite that its interests would be safeguarded. It was a vital function served by Canada’s Liberal Party over their long, successful history: cushioning discontent in every generation in which it has peaked, like a shock-absorber for the establishment.

Judging from Monday’s English-language leaders’ debate (the last of the current electoral campaign), Liberal strategists continue to believe that, in order to win, Trudeau must persuade Canadians that he is serious about addressing inequality.

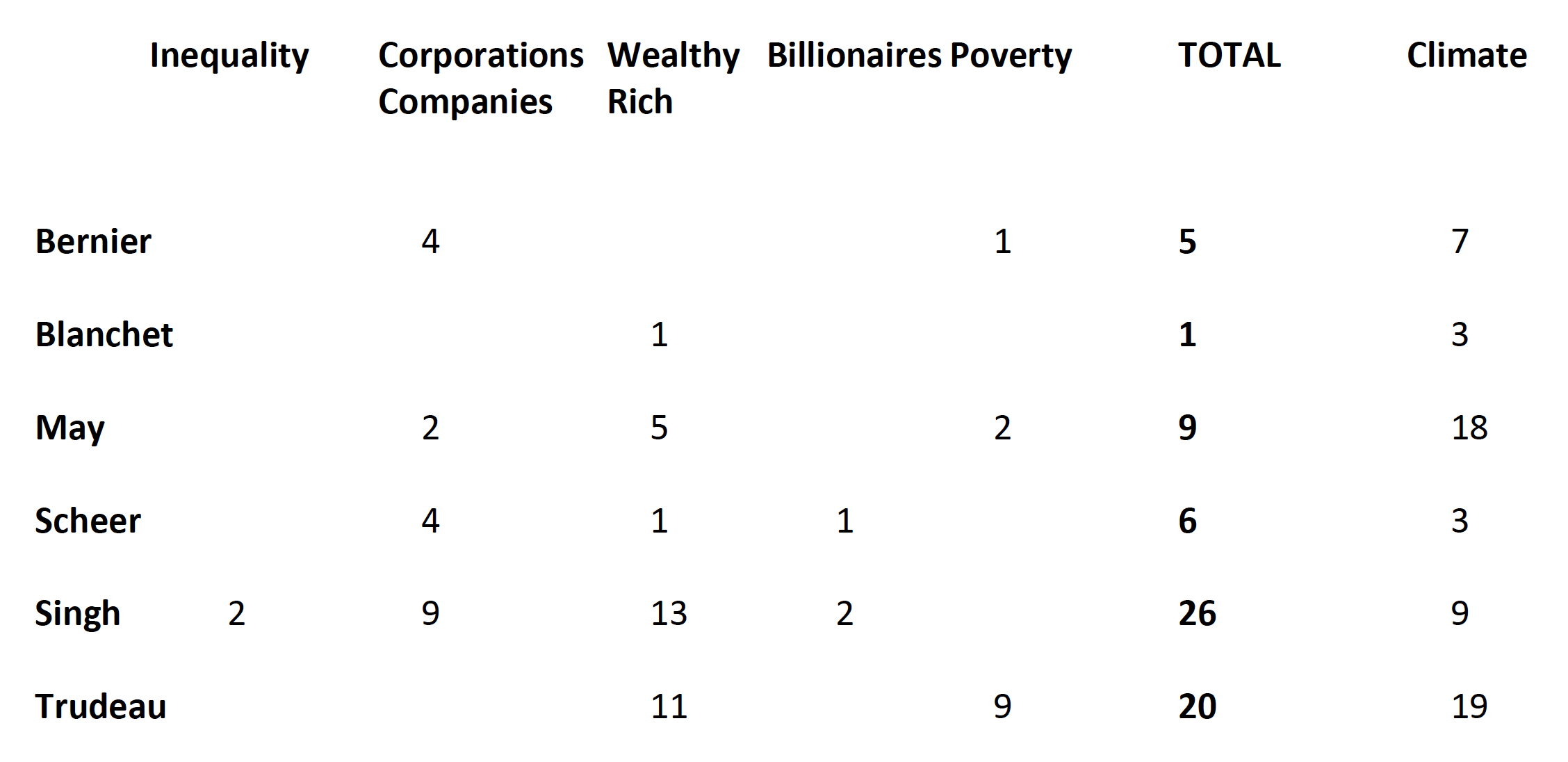

The chart below shows the frequency with which each leader employed the terms “inequality”, “wealthy” (or other terms derived from the term “wealth”), “rich,” “billionaires” and “poverty” during Monday’s leaders’ debate. For comparison purposes, the chart below also shows the frequency with which leaders employed the term “climate” — a dominant theme of this electoral campaign.

As the chart above reveals, Trudeau employed the language of inequality a total of 20 times in Monday’s debate, and was surpassed in the usage of that language only by NDP leader Jagmeet Singh.

Despite making the second highest usage of that language, however, Trudeau studiously avoided use of the terms “corporations” and “companies.” That may well have been due to the SNC-Lavalin scandal, in which Trudeau was revealed to have attempted to interfere in prosecutorial discretion in order to protect a large and powerful Canadian corporation.

Notably, Jagmeet Singh employed the language of inequality almost three times as often as Green Party leader Elizabeth May, whose language, unsurprisingly, highlighted the climate crisis.

By contrast, Conservative Party leader Andrew Scheer, People’s Party leader Maxime Bernier and Bloc Quebecois leader Yves-Francois Blanchet avoided discussion of inequality like the plague.

At one particularly revealing moment during Monday’s debate, voter Scott Marsden from Yellowknife specifically asked the leaders how they would address income inequality. Somehow, every leader but Jagmeet Singh managed to answer Mr. Marsden’s question without even using the word “inequality”. In fact, Mr. Singh is the only leader who uttered the word “inequality” during the entire two-hour debate, mentioning it twice.

In the real world, of course, there is often a vast disparity between political rhetoric and practice. The fact that a party leader makes generous usage of the language of inequality does not necessarily mean that that leader proposes policies that will dramatically reduce inequality or that such policies will actually be implemented.

A case in point is Canada’s top marginal tax rate. Earlier this year, a sitting member of the United States Congress openly advocated for a top marginal tax rate of 70% — an entirely sensible tax policy which enjoys majority support among American voters. Yet none of the six participants in Monday’s debate advocates a top marginal tax rate anywhere near the 70% level. As progressive as Canadian politicians are claimed to be, at least some members of the U.S. Congress seem far more receptive to steep increases in taxes on the rich than the six leaders who participated in Monday’s debate.

Nonetheless, the frequency with which party leaders employed the language of inequality at least gives us some insight into how they wish to be perceived.